One does not usually put ‘design’ and ‘hospital’ in the same sentence, but when interior architecture student Alana Inglis approached The Little Miracles Trust in June last year, she had no idea how much the NICU would impact her knowledge, skill and passion for architectural design.

For her masters thesis Alana aimed to bring the body back to the forefront of the architectural design process by focusing on intimate physical interactions between two bodies, but which two bodies?

It soon became apparent to her how unique the physical interaction between parent and child was and how design could help nurture and support this bond. With a family friend’s daughter born at just 28 weeks gestation, Alana was introduced to the concept of Kangaroo Care (the medical treatment based upon the essential nature of positive touch or ‘skin-to-skin’ care), and to a world in need of design. The Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) at Wellington Hospital would become her site with the bodies of parent and premature infant her testing ground.

Touch as Cure

After visiting the NICU it quickly became apparent to Alana how the current spatial layout of the harsh medical environment was dominated by machinery. There was a constant spatial negotiation between medical equipment, staff duties and space for parent/infant interaction. Seeing an opportunity to test her design theories by using Kangaroo Care as the platform for supporting a need for more intimate/private spaces for parent/infant bonding to occur, bringing the body back into the NICU.

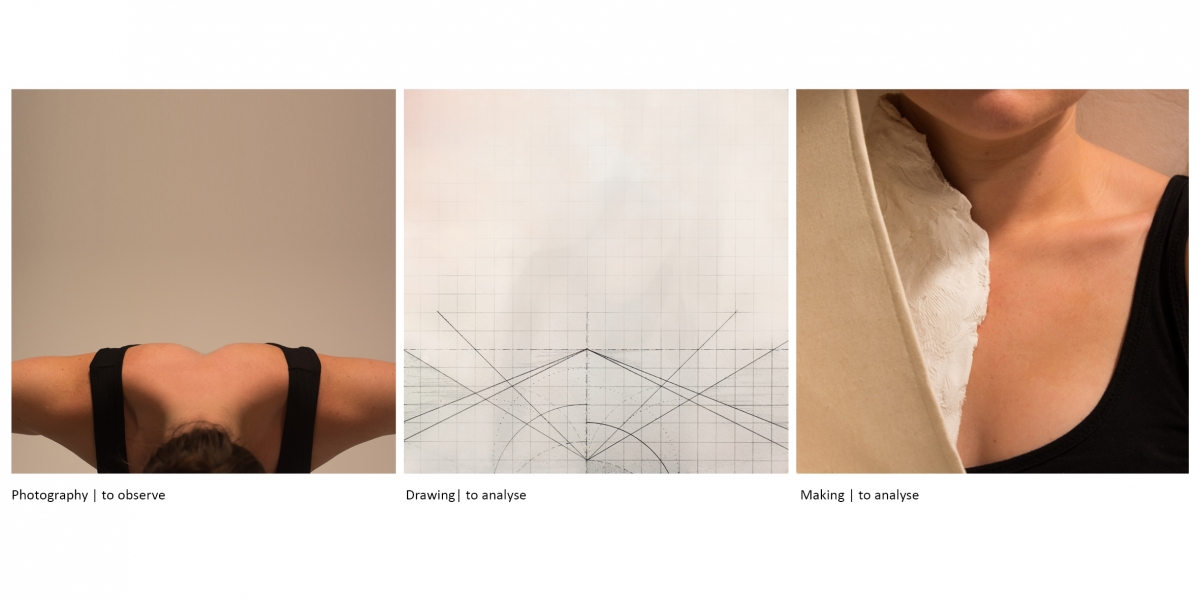

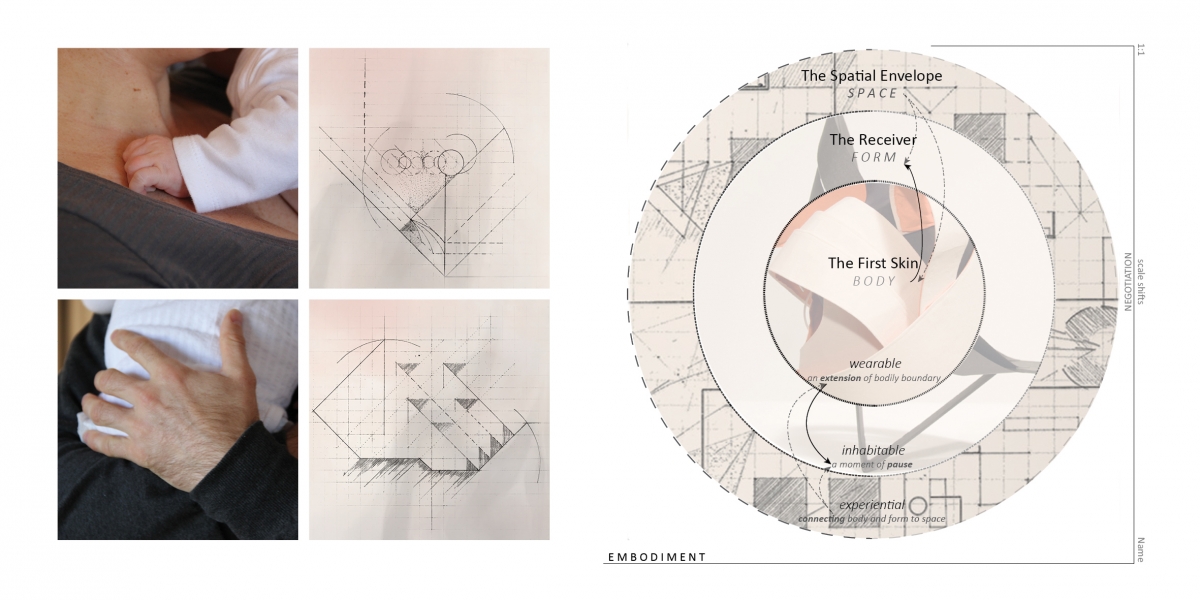

Following a process of physical modeling at the 1:1 scale Alana adopted spatial and furniture design techniques to develop concepts for wearable and inhabitable pieces for parents to occupy during this delicate interaction time with their infant outside of the incubator.

Her first piece of ‘wearable architecture’ was inspired by traditional Kangaroo Care in Colombia, and grew from a desire to extend the amount of time a parent might be able to hold their infant by providing better physical support to their head, neck, shoulders and lower back. Named The First Skin the design extends the physical boundaries of the parent spatially in a standing position (allowing small amounts of movement around the incubator sector boundary). A vest type element secures the infant to the parent’s chest leaving one arm free, the other is supported by a series of layered shoulder supports to hold medical tubing. Finally a large hood is wrapped up and around the parent’s head, focusing vision and dulling sound.

To help further support the NICU parent in a seated position (whilst wearing the Skin) The Receiver was designed as a replacement for the large bulky LazyBoy chairs that currently litter the cluttered NICU wards. The second design is a retrofitted recliner, which, once inhabited, further enhances a sense of intimacy and privacy for parent/infant bonding to occur via Kangaroo Care without obstructing the space required for medical equipment and staff duties.

Upon completing her thesis in April of this year, Alana dedicated her research to the infants, parents and staff of Wellington Hospital’s NICU who were so welcoming, enthusiastic and, most importantly, willing to share. The experience is one she will treasure as she moves in to industry, a reminder of the power of design when directed towards helping improve the lives of our most precious little bodies. The boundaries between design and medicine, between furniture and space, between architecture and design may blur at times but the goal remains the same – putting people first.

The Little Miracles Trust is very fortunate to now have Alana as one of our volunteers, and she is currently one of our team of website content editors. Alana, thank you for your continued support of the Trust.

Thank you to The Little Miracles Trust and to Tasia without whom my thesis would not have been possible. Your time, kindness, dedication and good work inspires me to continue using my design skills to help make a better world.

Alana

Below are some images from Alana’s thesis:

All images provided with the consent of Alana Inglis and must not be reproduced without her consent.